Over the last 20- or 30-years information about the critical need for exercise to support good physical health has made profound impacts on how people view fitness today. Everyone knows that they need to exercise and to choose not to is to choose to accept the risk of the many negative health consequences of living a sedentary lifestyle. Basically, the message is: if you do not do some type of exercise it is only a matter of time until something will go wrong with your physical health. This message is powerful.

Amazingly, as powerful as this message is, it is only part of the overall picture of how important exercise is in one’s daily life. What we don’t usually hear about but is equally as compelling is how beneficial exercise is for our mental health. Not exploring the benefits of exercise towards mental health is a missed opportunity towards better mental health and to strengthen the justification for beginning a regular exercise routine. Assessment of one’s physical fitness should be a major contributing factor when assessing mental health issues and how to treat them. Psychologist Leslie Korn says, rather tongue and cheek, that if everyone did 20 minutes of aerobic exercise every day, we probably wouldn’t need psychologists (Korn, 2016).

Neuroscientists Wendy Suzuki (2018) says that exercise is the most transformative thing that you can do for your brain for the following three reasons. Number one: it has immediate effects on your brain. A single workout will immediately increase levels of neurotransmitters like dopamine, serotonin, and noradrenaline, which can uplift mood and improve focus and reaction times. Number two: long term exercise improves attention functionality in the prefrontal cortex and increases volume in the hippocampus (which helps long-term memory). And third: regular exercise provides these benefits for the long-term. Like building a muscle, the brain retains the benefits of exercise by getting stronger and functioning better, particularly related to cognitive function and memory.

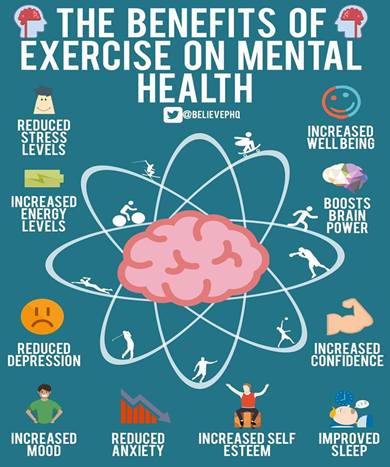

At a summary level, the benefits of exercise to promote stable mental health and to reduce symptoms of existing mental health issues are substantial. Physical exercise is highly effective at lowering stress rates and reducing depression symptoms compared to individuals who are less active (Chekroud & Trugerman, 2019). Longer durations of exercise with greater frequency, shows a progressive reduction in depression symptoms, anxiety, addictions, eating disorders, trauma disorders and PTSD. Additional benefits include weight loss, contributing to better self-esteem, better sleep, increased energy, increased mental clarity and positivity, and improved social relationships. These benefits are incurred because the movement of the body stimulates the central nervous system; increasing the release of endorphins and neuropeptides which can suppress your perception of pain and improve your mood. Additionally, during physical exercise, serotonin is released by the central nervous system (CNS) into your bloodstream. This neurotransmitter is that “feel good” response associated with happiness and well-being, positively affecting your overall physiological and psychological health and improving your overall mood. Regular exercise also helps to regulate the release of melatonin and cortisol, improving your sleeping patterns and regulating your food intake by balancing hormones responsible for suppressing or increasing appetite.

While these listed benefits are impressive in and of themselves, there are often many other residual benefits that indirectly affect mental health, like reducing insulin-resistance and improving glycemic control, which relates to mood and stress (Short, Pratt, & Teague, 2012), improved bone-density and reduce risk for heart disease, autoimmune disorders, and chronic headache and fatigue.

To some, exercise just sounds like such an unpleasant endeavor, but there are so many ways to incorporate exercise or body movement into one’s life, there is no reason not to include it. According to the U.S Department of Health and Human Services (2019), adults should be doing 150 to 300 minutes per week (2.5 to 5 hours) of moderate intensity aerobic physical activity and include 2 days a week on strength training, or anerobic exercise. These recommendations are for the average adult, so adjustments should be made for age, weight, and current fitness levels. Bottom line is any activity is better than none, but the above HHS recommendations can provide a target for continuing to increase the levels of fitness in daily life.

Explore exercise in the great outdoors

TIPS FOR IMPROVING WEEKLY EXERCISE

- Start out slowly and don’t take on too difficult of a goal in exercise (i.e. doing 90 minutes of PF90 or running a ½ marathon), Simply start slow with some twisting, shaking, stretching or squatting, in intervals throughout your day.

- Find times during your day to add a few 10 min bursts of physical activity. Set the alarm early if you need to wake earlier to begin your day with 10 minutes.

- Opt to take your meetings out of the office and “walk and talk,” or walk during your lunch hour.

- Turn on your favorite tunes and add dance breaks into your workday.

- Or, put on your favorite tunes and play your meanest air guitar or drum solo.

- Go on mall and shopping walks; increasing your pace as you get stronger.

- Recruit an accountability workout buddy. Enroll your colleagues, family and friends. Get a whole group together for even more fun!

- Find a professional trainer to assess your physical abilities and help design a workout program with assisted coaching and accountability.

- Recap your results daily. Track your goals, accomplishments and progress to keep yourself motivated to keep on track.

- Learn to say no to activities and thoughts which may lead you astray from your exercise goals.

- Go Outside!! Utilize the additional healthy benefits of being outdoors to enhance your exercise.

- Explore! There are so many opportunities for exercise. Find something you really love to do. Some ideas are yoga, qi gong, martial arts, kickboxing, boxing, hiking, swimming, water aerobics, join a recreational sports team, walk your dog (or cat), sprint runs, biking, get a basketball goal for your driveway, dancing, fitness competitions with family members.

- Rough housing with your kids or friends. Put together some leg or arm wresting contests.

- Cleaning! When it’s time to clean – CRUSH IT!! Put extra movement and vitality into your regular cleaning routines. Do squats while doing the dishes and finish off with some sink leg raises.

- Go to the playground! Use the monkey bars, climb, swing, and sprinkle in a couple of lunges or jumping jacks in between.

- Go for a long walk while listening to your favorite book on audio.

- Make whatever you do one of your favorite things to do. Consider this time for yourself and remember why you are doing more exercise. When the voices say no, just decide ahead of time to do it anyway!

References

40 ways to exercise without realizing it: Make exercise FUN! (2020, March 10). Retrieved from https://www.nerdfitness.com/blog/25-ways-to-exercise-without-realizing-it/

Chekroud, A. M., & Trugerman, A. (2019). The opportunity for exercise to improve population mental health. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(11), 1206. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2282

Films Media Group. (2018). Tedtalks: Wendy Suzuki—the brain-changing benefits of exercise. Films On Demand. https://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=18566&xtid=160843.

Korn, L. (2016). Nutrition essentials for mental health: A complete guide to the food-mood connection. W. W. Norton & Company.

Physical activity guidelines for Americans. (2019, February 1). Retrieved from https://www.hhs.gov/fitness/be-active/physical-activity-guidelines-for-americans

Short, K. R., Pratt, L. V., & Teague, A. M. (2012). The acute and residual effect of a single exercise session on meal glucose tolerance in sedentary young adults. Journal of nutrition and metabolism, 2012, 278678. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/278678